- Home

- Simon Turney

Commodus Page 13

Commodus Read online

Page 13

So it went on as things settled upon their return: I played mistress to Quadratus and Commodus drank in the adulation of his peers, and rarely did we meet, never in private.

The festival in October that is known as the Ides of Hercules – no coincidence there, I am certain – came around and was celebrated by the emperor and his heir. We were far from the Circus Maximus, where the October Horse was busily being sacrificed to Mars, but the emperor mirrored the sacrifice in Carnuntum. I could imagine my mother back in Rome, hiding away from such pagan blasphemy and praying by rote. I am made of different stock, and I simply cast up an apology to the Lord in advance and then enjoyed the festivities. The world in which we live is too complex to survive with such rigid thinking as my mother’s, and I was not the pliant girl I had once been.

Commodus and his father were honoured at the festival. Sufficient senators were with the court to confer titles upon the imperial personages, and both father and son were granted the title ‘Germanicus’ for their definitive victories. I watched Commodus receiving his honours as the poor horse busily bled dry nearby, and my heart soared to see him becoming the man I had always imagined he would be.

I could not speak to him that night, for his attendance at all times was expected, and Quadratus needed me, anyway. But the next day, when all was quiet once more and the festival over, finally the prince came to my rooms. Quadratus was busy ingratiating himself with the emperor, and I was alone when Commodus came, his Praetorian escort waiting patiently outside my door, out of earshot.

As he stood in my room and the door was closed behind him, I realised I had seen at the feast only what he wanted me to see, what he had wanted everyone to see. Now, close up, I noted a certain hollowness about the prince’s eyes. He was not suffering as he so often did – I had seen it often enough to recognise the symptoms, after all – but still he wore a mask of contentment that no one else seemed to notice.

‘What is it?’ I asked. I wanted nothing more than to hug him, but I had not seen him for a year. He had left a troubled prince and had returned a victorious general. It was hard to reconcile. For him as well, apparently.

‘What do you mean?’

I frowned. ‘You are not as happy as you make them all think. I can see it in your eyes. Your mask slips from time to time.’

He gave me a weak smile. ‘There may come a time when I regret you being able to see into my heart, Marcia.’ Something about that sentence chilled me, but I overrode it as he sighed and stretched. ‘It seems I am good at war.’

‘All of Rome is aware of that, now,’ I smiled.

‘My father berated me for becoming too involved. “A commander does not actively draw a blade and take part in war,” he told me. I reminded him of Caesar, of Tiberius, of Vespasian and others. Men who had done just that. Once upon a time to lead Rome was to fight. Still, I fought, and I led. I strategised and gave orders. I was every bit as much a general as Pertinax or your . . . or Quadratus. Better than he, for Quadratus is no soldier. I am, it seems, made for war.’

I felt cold at that notion and opened my mouth to reply, but he waved me to silence and sagged. ‘No, that is the problem, Marcia. I am made for war, but I simply do not want to be. War is not a thing to be wished or sought. It is every bit as much a disease as the Parthian plague, ravaging our people and killing indiscriminately. I do not like war. Father intends to continue his campaign next year, to press on against other tribes in the region and make the Danubius secure for all time. As though war could ever settle a border permanently. I do not want to fight on, Marcia. The Iazyges and their ilk could be bought over with concessions and gold instead of blood and sacrifice. If it were I, I would be doing just that and sending our men home.’

I was proud. Just listening to such reason, I was proud of my prince. He truly was the son of the great philosopher emperor, with the good of his people at heart. But it was not his decision to make, and the emperor believed the campaign needed to go on.

‘I am done with war,’ he said quietly.

And he was. While the emperor planned to stay in Carnuntum and proceed with a fresh campaign the next year, Pompeianus surprised us all by persuading the emperor that it would be better for the non-combatants and the extended familia with the court to return to Rome. The winter last year had been hard and, in addition to the still present effects of the plague, the risk to the imperial family and the less martial members of the court was too strong to ignore. The emperor, perhaps mindful of the tenuous nature of imperial succession, and remembering the three days of Verus’ vicious demise, commanded Commodus and a number of other courtiers to return to the capital. Thankfully, Quadratus was one of them. I fear that in addition to his lack of talent as a soldier, his attempts to make up for it with sycophancy and constant attention had driven the emperor to push him away. Quadratus was crestfallen and miserable.

As winter’s clutches descended on Pannonia, we moved south once more.

VIII

A MAN WHO WOULD ONE DAY BE EMPEROR

Centum Cellae, ad 173

Despite my feeble attempts to avoid the sea, Quadratus would hear nothing of it. We left Carnuntum on the kalends of December and moved at a reasonable pace. This time we were not hampered by slow-moving military units and their endless wagon train. This time we moved at the speed of private citizens, and even the soldiers with us were mounted, part of the imperial horse guard.

We followed almost the same route in reverse, crossing the hilly terrain of Pannonia and heading for north-east Italia. There we crossed the flat plains of Venetia and the narrow northern stretch of the mountains, making for Pisae. I noted oddly that Commodus’ mood began to become a little erratic as the journey went on and it was only when I found him one morning looking at the icy, frozen surface of a horse trough while our mounts and vehicles were being made ready that I remembered how the winter’s frost and chill were a constant reminder to him of Fulvus. I tried to keep his spirits up and, to some extent, I succeeded, but the connection was always there below the surface, waiting to reappear as long as we remained in winter’s grip.

Finally, we took ship at Pisae. It is a near two-hundred-mile journey down the coast from there to Ostia and civilisation, and I spent days shivering at the thought of that vast swathe of water beyond the ship’s all-too-thin hull. In the end, even Quadratus, who rarely thought of more than himself, softened to my fears and did not argue when Commodus persuaded the small party to cut the journey short and dock at Centum Cellae a day early, making the last forty miles to the capital by road.

We settled in at that port city in Januarius and prepared to stay the night while our escort arranged transport for the last leg. Our arrival in Centum Cellae was so unexpected that the authorities did not have time to prepare an appropriate welcome for the prince and his entourage and struggled to put together a banquet in time. Commodus did not really care. We were not in search of pomp or glory, but of comfort and warmth.

As the best quarters in the city were made ready for the imperial party and the members of the ordo rushed around making all just so for the banquet, Commodus simply made for one of the city’s bathhouses, which was ready to close at the end of the day. Quadratus, robbed of the chance to fawn at his emperor, followed the prince and joined him there, and I was taken along with them. A small group of Praetorians protected the bathhouse to keep the prince safe.

I paused at the entrance, certain that the two men would not want a low-born woman in there with them, despite the mixed nature of such establishments. There was no one else there, the last bathers having left recently, and the place would undoubtedly have been closed to any less important visitor. As it happened, Commodus waved me in. Slaves appeared from somewhere, confused by the sudden change in routine when they were supposed to be closing up for the day, but they managed to provide towels and clogs and all the paraphernalia of bathing.

I waved away the towel and the re

st. I like baths. I like to relax in the warm and to be clean and primped, but days at sea had got to me and, despite the luxury available, I had not the remotest urge to sink into yet more water. Instead, I found a manicure kit and prepared to look after my hands, which were suffering somewhat from inattention and the barbaric conditions of Pannonia. While my place as Quadratus’ mistress had left me acutely aware of the importance of looking the way he would expect me to, which was almost certainly in that very same way that Mother had once warned me against, the cold lands of the north had been far from ideal for maintaining my appearance to its utmost.

I followed the two men, now wrapped in towels, through the rooms. The floors were not as warm as usual, and I reasoned that this was because we were here after the place officially closed. The failing in the furnaces became apparent as we entered the caldarium and the two men moved to the water’s edge, dropped their towels and slid into the bath.

‘Shit,’ Quadratus barked, then stared in horror at the realisation he had sworn so basely in the presence of the prince.

Commodus waved it aside, clutching his shoulders and wrapping his arms around himself. ‘This hot bath would have to warm considerably to just be tepid,’ he agreed.

Certainly, there was no steam rising from the water into the cold winter air as was the norm, and the floor was barely above outdoor temperature.

‘Marcia, tell someone . . .’ Commodus began, but at that moment a slave entered the room, bent double in a careful bow.

‘Majesty, we were not expecting a visit at this time.’

Commodus nodded. ‘This water is cold. You’ve not been closed that long. Get the furnace slave to work.’

Quadratus snorted. ‘Cold as ice, in fact. Bet it’s forming on the surface already. Maybe you should throw the slave into the damned furnace for good measure.’

The attendant rose from his bow, eyes wide, taking this for an imperial command.

I saw Commodus’ face then, though. Saw what passed across it, and shivered. The notion of ice and a frozen surface had cut through Commodus and torn him from Centum Cellae, throwing him forty miles distant and back through the years to his twin, trapped beneath that frozen sheen. All my work across the mountains keeping his spirits up, only to have it all ripped apart by a chance remark from Quadratus, who should have known better. The prince was distracted suddenly, pain flooding his eyes, his gaze on the surface of the water as though he saw Fulvus beneath it.

‘I said he should burn the slave,’ Quadratus repeated, with a horrible snarl.

‘Quite right,’ Commodus replied, paying not a jot of attention, eyes locked on the water.

I frowned, but Quadratus leapt upon what sounded like imperial sanction. ‘Do it. Send him in.’

The slave backed out, a horrified expression upon his face, and I crossed to where the prince was standing, head cocked to one side.

‘Commodus?’

‘Mmm?’

‘You can’t really mean to burn a slave?’

‘What?’ He was distracted still, not really listening to me, replaying the death of his twin in his head as he had done so many times over the years. I was torn. There was danger here in the path down which his thoughts were taking him, and I knew what could come, but a slave was hurrying down into the bowels of the bathhouse with orders to throw one of his companions into a furnace. As a Christian, I could not let such a thing happen. As a human, I could not.

The decision was made for me as Quadratus waved me away. ‘Fetch wine while we wait,’ he commanded.

I needed no further urging. I left the room and hurried after the slave. I found him by a small door marked as the entrance to the furnace tunnels. He had stopped and was addressing a man in a plain, if good-quality, blue tunic who had an official, competent air about him.

‘He asked what?’ the man demanded of the slave.

‘That I burn Caro in the furnace for letting the water get too cold.’

The man in the blue tunic shook his head in wonder. Behind him, two men were standing impatiently, holding what appeared to be a deflated sheep. One of them cleared his throat, and blue-tunic turned.

‘I cannot accept it. Take it back and tell your master that a rug is flat and does not still contain parts of the animal. If I’d wanted a carcass, I’d have asked for one.’

The bath slave made desperate noises, and, with a long-suffering sigh, blue-tunic turned back to him. ‘I don’t care if it’s a prince or the emperor or mighty Neptune himself, I am not about to throw an expensive slave into a furnace just because they have the audacity to turn up when the baths are closed.’

‘About this rug—’

He spun again. ‘It is not a rug. It is a badly squeezed sheep. The answer is still no.’

‘Sir, the furnace . . .’

And back to the slave. ‘No. No slaves in the furnace.’

He paused, and a strange smile spread across his face. He turned back to the two men. ‘I will take it, after all, though tell your master it is not what I wanted, and I will pay only half.’

They looked as though they might argue, but clearly blue-tunic was determined, and they shrugged, dumped the deflated, filleted sheep on the floor, and left.

Blue-tunic pointed at it. ‘Throw that in the furnace.’

‘Sir?’

‘I know princes and nobles are educated differently to the rest of us, but I doubt even the emperor could tell the difference between a burning slave and a burning sheep when it leaks up through a floor.’

With a bow, the slave heaved up the heavy carcass and struggled off through the door with it. The man in the blue tunic sighed and rubbed his head vigorously, turned and noticed me for the first time. He flinched. I was clearly important, from my attire, which meant I was almost certainly connected to the prince and the noble he had just insulted in passing.

‘I’m not sure what you heard there, my lady?’

‘Enough to label you clever and resourceful.’ I smiled. ‘I was coming to find someone in an attempt to stop such madness. It is not the prince’s order, or would not be if he were thinking straight. He will thank me – and you – later. Quadratus not so much, so let’s maintain the fiction this Caro lad was burned, eh? How fast can you warm the bath and floor?’

The man, still cowering a little since I was important, shrugged. ‘It will be quick. The bath and floor surfaces cool swiftly when the furnace dies, but the ambient temperature within the hypocaust will still be high and it will not take long to bring it back up. Like a pot of water that’s been recently boiled, which does not take long to make bubble again.’

I liked this man straight away. Clever, thoughtful and straight. There was a chance here to repair the bathhouse’s reputation and to help break Commodus of the strange spell under which he had so suddenly fallen. Bathhouses had entertainment for their guests, and this was quite a large one. Perhaps it had its own entertainers?

‘Do you have wrestlers?’

The man’s brow folded. ‘We do. They are instructors and masseurs as well, but they put on shows for the clients as required.’

‘The prince loves wrestlers. Have them attend. And bring good wine and snacks. Beef. He likes beef. What is your name?’

‘Saoterus, my lady.’

‘Be quick, Saoterus.’

I returned to the baths to find Commodus sitting on the water’s edge with a faraway look in his eye. Quadratus clearly had no idea what was going on with the prince and stood in the water helplessly. I was gratified and impressed to note that, even in such a short time, the floor was already noticeably warmer. The bath would be slower to warm up, of course, due to the volume.

‘Where’s the wine, girl?’ Quadratus snapped.

‘They only had a local cheap stock,’ I lied glibly. ‘The baths’ master has gone to fetch wine of appropriate quality.’

My master

harrumphed at me irritably, but he would not argue, for he would rather have good wine slowly than poor wine fast, which is something I have found to be a general facet of Roman nature. Moments later, a slave entered with repeated bows and announced, for the prince’s entertainment, the ‘renowned Sardinian wrestlers Narcissus and Falco’.

Two men with more muscle than any human being had a right to, entered, bowed to their tiny audience, and shuffled along the wall to an area with adequate room for a match.

Quadratus’ face was a picture of plum-coloured fury. ‘What is the meaning of this? Bringing killer slaves into the prince’s presence? I have a mind to . . .’

He tailed off into silence as Commodus, looking present and alert for the first time since he entered the bath, waved him down. ‘Quiet, man. I am intrigued.’

And that was it. Commodus was back. I had seen the slippery descent ahead of him and managed to grasp him before he fell. I was sure I was becoming mistress of his melancholia, able to control it and buoy him up when needed, just as my opposite number Cleander was able to constrain his worst temptations.

The wrestlers fought three times, the third time ending with an ignominious fall by Falco into the now-warm pool that had Quadratus scowling just as Commodus roared with laughter. As the bedraggled Sardinian dragged himself from the water sheepishly, the other man bowed low, a hundred muscles rippling.

‘Narcissus, was it?’ The prince smiled.

‘Yes, Majesty,’ the wrestler replied in a thick, almost Gallic accent without raising his gaze.

‘You are good. Wasted in this place. You need to be in Rome, man.’

I could see a wave of disappointment wash across sodden Falco’s face, but as Narcissus straightened, I caught his eyes, and could see something there. He had been showing off for the emperor. He had not been meant to throw Falco in, but had done so to prove his worth. Slaves rarely get the chance to attract the imperial gaze after all. He was shrewd, this Narcissus.

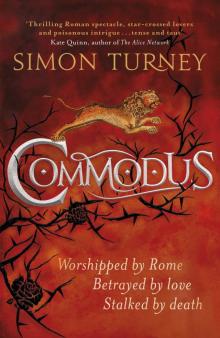

Commodus

Commodus